STREET ART BETWEEN WORDS

By Pedro Soares Neves

1

MY CONCERNS

I have two main concerns that drive my contribution to Street Art research in general and in this essay I will try to use them to analyze the “Post-Street Art” definition, as proposed by Nuart Festival.

1.1

My first concern is about the street; the urban fabric; the city; the landscape; open air; the outside; the “nature”; the physical “things” that surround us collectively and the space between buildings (including the building’s “skin” i.e. walls, floor (as stage and support for life), objects, and visual signs).

What concerns me about space is how we deal with it so that we can address our needs. How did we do it in the past, how do we do it now, and how will we do it in the future? How do planning and usage interact, both historically and today? This raises questions of durability; environmental awareness; sensitive construction of space; tension between conflicting usage; territorial narratives; organizational social structures; norms; and the absence of rules as policy. Without going into too much detail on the subject here the limits of open and closed space is also one of the most fascinating discussions in architecture and urbanism, and one that can be useful for the relation of Street Art (or Post-Street Art) in the context of a cultural institution such as a gallery or museum.

1.2

My second concern is about research methods; consolidation of knowledge; understanding where the most concrete and objective facts are; gathering knowledge about Graffiti and Street Art; looking upon planning and usage; and how all these factors interact with academic tools focused on Graffiti, Street Art and urban creativity in general.

1.3

Both concerns go in the same direction, generically tending to help us build a better environment or, in other words, using the resources available in the best way possible. Both foster ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’ encounters. This dynamic of ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’ has been developed by several galleries, museums and cultural infrastructures towards Graffiti and Street Art to find ways of building knowledge and bridges for encouraging dialogue. But the purposes are very diversified: from ethnographic, to commercial, to conservationist you can find a full range of adopted approaches. This diversity and engagement contains risks, and one of the most evident is the unclear definition of concepts such as Graffiti and Street Art.

2

WHY CHANGING

Generally it can be argued that a stable, consensual new definition is needed for all that is happening an and around Street Art. Misunderstandings can be exacerbated by less informed organizations and events, and various solutions have been used to fill the gap, ultimately contributing to the instability of the concept and in constant negotiation of the terms ‘Street Art’, ‘Urban Art’, muralism, or even placing Street Art in wider discussions such as public art, or just contemporary art.

2.1

The intention for adopting a new terminology is key

2.1.1

‘Post-Street Art’ is something that can be read in opposition to Street Art. Although not necessarily interpreted in this sense, the historical usage of the “post-something” prefix in arts and architecture is often in opposition to the past.

2.1.2

‘Post-Street Art’ as something with specificities (such as ‘commissioned’) can be another thing, generating doubt about the kind of relationship that exists between Post-Street Art and Street Art. But who manages this relationship?

3

CONTRIBUTIONS

In an attempt to avoid further confusing the issue, I share two concrete cases that emerge from my two concerns outlined above: post-modernism in Architecture and Post-Graffiti.

3.1

Complexity and contradiction in post-modernist architecture.

To cut a long history short, Mies maxim of “Less is more” was replaced by Venturi as “Less is a bore” in his attempt to define post-modern architecture. In his writings Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture and Learning from Las Vegas, Venturi constructs some of the main theories of post-modernist architecture, where it’s mentioned that ornamental and decorative elements “accommodate existing needs for variety and communication”.

For the purpose and length of this essay, it can be extracted that in the case of post-modern architecture there’s a clear position against the functional and pragmatic modernist architecture. It’s interesting to note that Street Art also “accommodates existing needs for variety and communication”.

3.2

POST-GRAFFITI AS RESEARCH THESIS

In the PhD thesis El Post-Graffiti, su escenario y sus raíces: Graffiti, punk, skate y contrapublicidad. Madrid, 2010, Francisco Javier Abarca Sanchís (in 200 pages dedicated only to the Post-Graffiti concept) delineates typologies, methods, and aesthetics, among many other factors. To synthesize this in one sentence is not possible, but for the purpose of this essay maybe the factor that’s most relevant is that Javier identifies post-Graffiti as a ‘consequence’: a successor to Graffiti.

So, in this case we have the usage of the word “post” as a consequence: a successor of a certain subject. The relevance of Post-Graffiti in relation to the analysis of Post-Street Art is that if Post-Graffiti is synonymous with Street Art, so Post-Street Art will certainly be something else.

4

CONCLUSION

Post as “commissioned” or “after” depends on the intention. There are examples of very distinct approaches to the “post” usage. Designations that try to encapsulate the distinction between Graffiti, Street Art, and commissioned “Street Art” are already abundant. They reply to the need that it’s deemed necessary to protect Graffiti and Street Art’s particular characteristics. Nuart is one of the places were the Post-Street Art definition can emerge with structure, and this will be useful for designating (commissioned, detached or bought) traces of the unnamable, intrinsically human, non-commissioned, environmental, and visual signs that come to my mind when we are talking about Graffiti and Street Art.

1 GEHL, J. (1987) “Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space”; Copenhagen: The Danish Architectural Press

2 BENGTSEN, P. (2014) Street Art World. Lund: Alemendros de Granada Press.

3 NEVES, P. Soares - Urban Art- difficulties in its typification, and evaluation methods CITTA 3rd Annual Conference on Planning Research, Porto 2010 link: https://www.academia.edu/1075695/Urban_Art-_difficulties_in_its_typification_and_evaluation_methods

4 ROBERT Venturi, DS Brown, S Izenour Learning from Las Vegas: the forgotten symbolism of architectural form, MIT press, 1977.

5 SCHACTER, Rafael - Ornament and Order: Graffiti, Street Art and the Parergon. Ashgate Publishing, 2014.

6 ABARCA, Javier - El postgraffiti, su escenario y sus raíces: graffiti, punk, skate y contrapublicidad. Madrid: Universidad Complutense, 2010.

IMAGE IN HEADER by NEVES, P. Soares, based on iconic image of Post Modern Architecture in: ROBERT Venturi, DS Brown, S Izenour Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form, MIT press, 1977.

FIGHT CLUB - MAKING HISTORY WITH 'POST-STREET ART'

Fight Club was established in 2012 as a way to introduce difficult topics in a more relaxed environment condusive to public engagement.

NUART PLUS 2016 PROGRAM

This year’s Nuart Plus symposium will explore the topics of ‘Utopia and Rights to the City’ and ‘Dada, Art and Everyday Life’ on the 500th anniversary of Thomas M...

NUART PLUS 2016 - DAY 1 - KENNARDPHILLIPPS Talk & Q&A Session

Utopia, from the artists perspective

Artist presentation by Kennardphillipps, followed by a Q&A session with Carlo McCormick.

NUART PLUS 2016 - DAY 1 - NUTOPIA

Nutopia panel debate

Discussion led by: David Pinder

Panel: Pedro Soares Neves, Peter Bengtsen, Emma Arnold

NUART PLUS 2016 - DAY 2 - JEFF GILLETTE AND HENRIK ULDALEN

Panel debate: The Borders of Street Art

Artists presentations by Jeff Gillette and Henrik Uldalen, followed by a Q&A session with Evan Pricco

WOMEN’S RIGHT TO THE CITY

By Emma Arnold

SUBVERTING AND CONTESTING THE MASCULINE AND SEXUALISED CITY

CARLO McCORMICK (US)

Pop culture critic, curator, and Senior Editor of PAPER magazine

EMMA ARNOLD (CA)

Research Fellow, University of Oslo Department of Sociology and Human Geography

PEDRO SOARES-NEVES (PT)

Founder, Lisbon Street Art and Urban Creativity

PETER BENGTSEN (SE)

Art historian and sociologist, Department of Arts and Cultural Sciences, Lund University

DEBATE: WHO HAS, OR SHOULD HAVE, THE "RIGHT TO THE CITY"

Henri Lefebvre’s "right to the city" concept provokes us to consider how we might remake the city with the goal of creating more just and ideal societies.

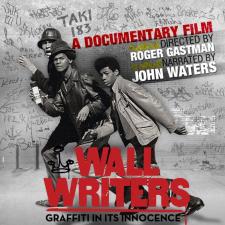

WALL WRITERS FILM SCREENNG

Nuart Festival and SF Kino Stavanger present Wall Writers: Graffiti in its Innocence